Collecting Trip for Conservation

2020 Gene Conservation Tree Report on "Quercus boyntonii"

Noteworthy Observations:

Habitat

QUBO is reported to be endemic to sandstone outcrops of the Ridge and Valley Physiographic region. This effort found plants in a wider variety of sites than it is traditionally associated with. A thriving population was found in the woodlands of the Cumberland Plateau in Blount County. These plants did occur on and between the exposed rocks on the slope, but it was not in the upland situation where we had become accustomed to finding them. These plants grew right down to the scour zone of the Black Warrior River with pillows of sphagnum moss at their bases (Figure 18). According to the landowners, the roots and trunks of these lowest plants would have been submerged multiple times over the years during periods of high water flow. Not something we expected from a species that is adapted to survive the repeated oven dry conditions of an exposed rock outcrop in a subtropical Alabama summer. At the southern extent of our exploration we puzzled over the 3 lobed leaves of oaks on a sandy fall line hill that is definitely on the coastal plain. Moving between rock outcrops on the ridge of oak and Double Oak Mountain we were surprised to find QUBO growing with some frequency in the grasslands of the mountain’s south face and ridge tops (Figure 19). At the Hinds Road Rock Outcrop, diminutive specimens of QUBO have the appearance of natural bonsai (Figure 16).

Figure 18: Riparian QUBO habitat in the Cumberland Plateau Physiographic Region.

Figure 19: Savannah habitat where QUBO was found on Double Oak Mountain.

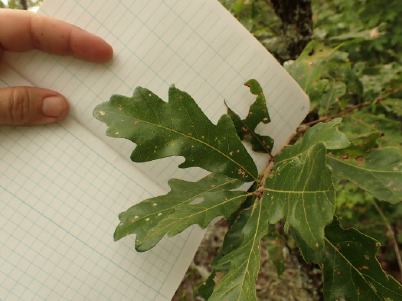

Herbivory

Figure 20: Three species of larval Lepidoptera were documented feeding on QUBO: Anisota sp., Acronicta increta, and Anisota virginiensis.

Fire Tolerance

Fire scars indicating a recent low intensity burn did not seem to have any negative effects on QUBO within the area of a natural fire on the south face of Double Oak Mountain. Similarly, specimens inspected within the burn unit of a prescribed fire on the Belcher Tract did not suffer any observable mortality as a result of the burn.

Figure 21: The trunks were charred to a height of 2m on the Pinus palustris (right) and the QUBO (center) indicating significant fire intensity. Healthy new growth on the QUBO suggests they possess a good degree of fire tolerance.

Figure 22: Charred trunk of QUBO and a single new stem emerging from the base of the trunk.

Growth Habits

This species is commonly described as a shrub or small tree; sometimes reach a height of 6 meters (20 feet) but usually smaller. During the surveys conducted through this grant, QUBO was observed growing as individual trunks, multi-trunk masses, coppices, clonal colonies, shrubs, and a variety of combinations of these growth habits. Further census work will provide a data set for statistical and spatial analysis that will provide insights into what actually is the most typical growth form for this species. We agreed that the plants seem to rest in these stages. We did not see plants in between these stages to make us think that QUBO behave like typical oaks with the potential to be a 15 m tree, simply growing toward that maximum size on predictable growth curve.

Figure 23: QUBO rhizomatous stems expanding colonially with no dominant leader.

Figure 24: Noah Yawn searching for acorns on a single trunk small QUBO tree.

Figure 25: Lynn Purser and Noah Yawn counting stems of a single trunk small QUBO tree with rhizomatous stems expanding colonially in Oak Mountain State Park.

Figure 26: Medium single leader QUBO tree with rhizomatous stems.

Figure 27: Noah Yawn searching for acorns on medium QUBO trees without rhizomatous stems.

Figure 28: QUBO exhibiting a multi-stem shrub form.

Figure 29: QUBO exhibiting a multi-stem copse habit.

Recognition of 5 Super-specimens

Among the hundreds of specimens observed and measured during the course of the team’s work with this species a handful of presumed individuals were documented that had grown to a scale far exceeding previously published limits for the species. All of these specimens have an exceptional amount of biomass, but that does not correlate directly to acorn production, as only one of the 5 seems to have produced an appreciable amount of acorns this year. Growth patterns and uniformity of leaf morphology led the team to deduce that these plants represented single individuals.

Figure 30: The Oak Mountain Monster: This presumed individual at Oak Mountain State Park has 52 trunks with an average dbh 12.7 cm and a fairly uniform height of 10 meters. It also has 179 stems that exist at the ground level with very little intermediate growth and extended 15 m along the ridge with a width of 10m.

Figure 31: Oak Mountainous Maximus: An amazing plant so large our entire team sat down to lunch under it’s branches and decided measuring it would require and entire day. The plant extended for about 35 meters along the ridge in a protracted oval shape about 15 m wide through much of its core. The number of stems and trunks could reach over one thousand.

Figure 32: Irondale’s Ironsider: The only Jefferson county super-specimen is the only one of the five that is not part of a thriving population. This makes it the most likely super-specimen to become a total loss at the genetic level. The property owner is very aware of the plant as it dominates his backyard. He repeatedly pushes back the non-native invasive species, but they persist.

Figure 33: The Blount County Beast: This EO is home to several vigorous mature specimens. This exceptional plant had found a location between and on top of a rock formation where it had attained a height and width of about 10 meters. The single trunk specimen had a dbh of 25cm. There were 30 smaller stems coming from the duff around the trunk, but none seemed to be attempting to grow into a tree form. Several hundred acorn caps were found under it, but it had apparently dropped many acorns early in the season and only 5 were collected.

Figure 34: Etowah Shelf Elf: An exceptional specimen 10 m in height. This one had 3 trunks with a maximum dbh of 24 cm. The presence of 64 surrounding stems are inconsequential compared to the mass of the 3 main trunks, and there was no intermediate growth or acorn production.

Presumed Hybrids Identified and Mapped

Quercus boyntonii x margarettae

Quercus boyntonii x stellata

Quercus boyntonii x alba

Quercus boyntonii x montanta

Figure 35: Quercus boyntonii co-occurring with Q. margarettae, and a presumed hybrid with intermediate leaf morphology.

Figure 36: Presumed Quercus boyntonii x alba.

Figure 37: Presumed Quercus boyntonii x montanta.

Figure 38: Presumed Quercus boyntonii x stellata.

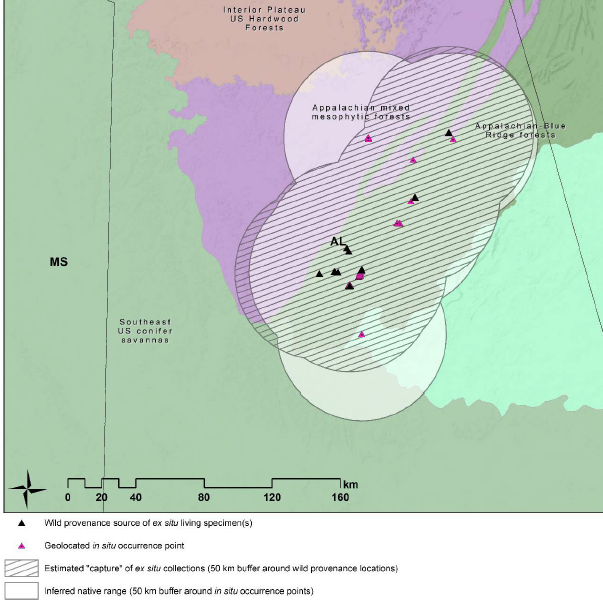

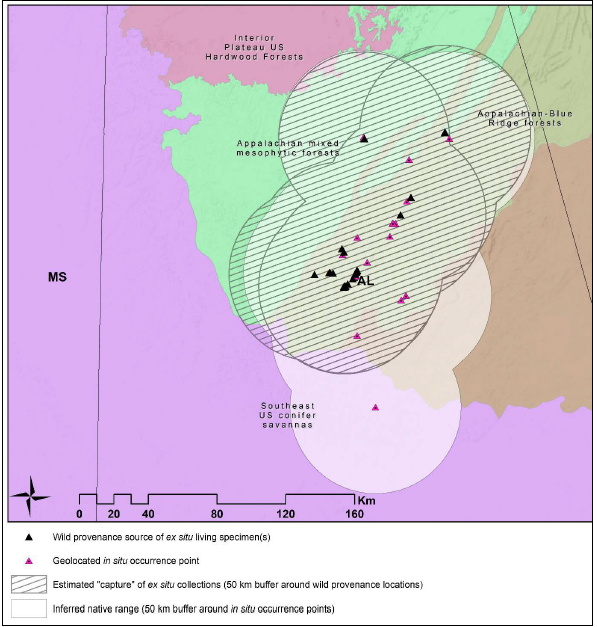

Germplasm collection

During this project, 667 acorns from 17 maternal lines from three populations at four locations were collected across three counties. Three additional counties were scouted and documented with herbarium vouchers. Germination rate of acorns and success rate from seed to two-year seedling will be recorded for the acorns planted at HBG and the institutions that received acorns have been asked to track the same information. Though some plants will likely fail between germination and landscape establishment, there is a good probability of many plants to survive, increasing representation of well documented, wild collected material of this taxon in cultivation. Future collecting activities will likely focus on targeted collecting from populations which were either missed during this project, or fail to produce a suitable amount of replicates in production. Additional research in both systematics and population genetics would be helpful to assist with more guided collecting and conservation efforts. Follow up work to document horticultural protocols and survivorship among participating institutions should inform future efforts to maximize success of efforts to conserve the species in ex situ collections.

Figure 39: Range and ex situ genetic capture map generated by Global Conservation Consortium for Oak Gap Analysis database Quercus boyntonii records before 2020 Tree Gene Partnership reporting.

Figure 40: Range and ex situ genetic capture map generated by Global Conservation Consortium for Oak Gap Analysis database Quercus boyntonii records after 2020 Tree Gene Partnership reporting.

Limitations and Future Directions

The good news for QUBO is that there are protected populations on state lands at the Northern and southern end of the species verified range; Forever Wild’s Hinds Road Outcrop Tract, and Oak Mountain State Park respectively. The reality for the core of the species range is that it has become severely fragmented by the continued expansion of the Birmingham metropolitan area. Increasing awareness of this AL endemic species could continue to yield new occurrences in this area.

Genetics work is going to be required to establish the validity of possible extensions of the verified range of the species. Potential expansion includes the new Autuaga county record vouchered on this trip, as

well as occurrences worth investigating in Cherokee and Dekalb counties. Analysis of genetic markers will also be needed to warrant the recognition of presumed hybrids seen and mapped during this project. Genetic analysis of copse form plants would be necessary to determine the actual number of plants as well because current census methods do not account for the possibility that soil pockets could be occupied by either one multi-stemmed individual or multiple individuals sprouting from the limited soil available in their habitat. Efforts to formally describe the presumed hybrids documented here would also require genetic analysis.

Completion of the census work would require detailed surveys of two relatively large populations: Blount County and Hinds Road Outcrop, as well as a population of unknown size in St Clair county. We have observed, and been notified of, sites surrounding these populations that would add to the count for the species. Once data has been collected on these specimens, statistical analysis will aid in determining what the true growth parameters are for the species, and the frequency of occurrence for the numerous growth forms observed and documented by this study. The census work would dovetail nicely with the need for germplasm collection from St Clair and Etowah counties. It would make an excellent future endeavor for the Tree Gene Partnership between the APGA and the USFS.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Matt Lobdell, Amy Byrne, and Emily Beckman for their support during the planning and initiation of this project. Appreciation goes out to Noah Yawn, Zac Napier, Frank Thompson, and Lynn Purser for volunteering on scouting and collection trips. Thanks again to Amy Byrne and to Katie Lawson for helping cross reference databases and generate maps for this report. Additional support appreciated from Scott Pardue, Dixon Brooke, Lauren Muncher, Michelle Reynolds, Pam and Ray Thompson, Colin Conner, Marc Harris, Mari Carmen, Alden Brindle, Brian Keener, Wayne Barger, and Al Schotz. Thanks as well to EBSCO, Oak Mountain State Park, Forever Wild, The City of Hoover, Camp Winnataska, The Alabama Natural Heritage Program, AL Department of Conservation and Natural Resources and numerous private property owners and managers who permitted access to properties for field work, and to APGA and USFS for creating the opportunity to work on this project.