The long, hard road for Hellbenders

Scientists spend years searching for giant salamander in Alabama

On this August day, the team of scientists canoed more than 8 miles down Sugar Creek and identified Wood Ducks and Great Blue Herons, River Cooters and hummingbirds. The team saw all manner of spiders and fishes, and countless wildflowers in bloom, but no Eastern Hellbenders.

On a hot, late August afternoon in 2016, an expedition of scientists carefully turned onto a narrow, one-lane, dirt road that ran parallel to the railroad tracks. Their trucks precariously balanced canoes and kayaks as they weaved a short distance marked by deep potholes. In single file, they arrived at the back entrance to the property, property owned by a family from scientist Jeff Garner’s childhood.

“The gate’s locked,” shouted Garner to the team. “I know another way in!”

Garner grew up in Lauderdale County, Alabama. A biologist with the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries, Garner’s local connections were the team’s key to accessing the more remote portions of Butler Creek, portions that run through private property.

The group, led by James Godwin, an aquatic zoologist with the Auburn University Museum of Natural History’s Alabama Natural Heritage Program, was searching for the Eastern Hellbender, the largest and one of the longest living salamanders in North America. A Hellbender can reach more than 2 feet long and can live for decades. Once found abundantly throughout its native range, which extends from northern Alabama and Georgia to New York, Eastern Hellbender populations are experiencing steep declines. In fact, the species was thought to be completely eliminated from the state of Alabama, but unconfirmed sightings in recent years have given scientists new hope that the species still exists in the state.

In 2015, another team of scientists working under Godwin’s direction found an Eastern Hellbender in Alabama in the Flint River, not far from the Tennessee border.

Over the course of the next year, Godwin continued to organize Hellbender expeditions but was unsuccessful in locating the creature a second time, despite the animal’s preference for a very specific habitat – swift-moving, clear-water streams or rivers with rocky bottoms in the northern Alabama, Tennessee River drainage basin.

On that summer afternoon in August, Godwin’s latest team had already explored another section of Butler Creek. The only animals they caught were a couple of turtles and a Midland Water Snake. No sign of the Eastern Hellbender.

Despite setbacks, no one on the team was complaining as the cooling waters of the creek were a welcome relief from the Alabama summer heat.

Facing a locked gate and no room to turn around, the caravan drove back down the dirt road in reverse and then continued several miles, circling the edge of the property before ultimately arriving at the main entrance.

Garner led the team down a long driveway, past a family home, and onto a barely visible trail, marked only by tire-flattened grass. At the end of the trail stood a rusting metal carport that shielded a couple of free-roaming house cats and an old sofa, and beyond that was Butler Creek.

The property owner had constructed a makeshift entrance into the creek using portable metal porch steps and conveniently placed layers of carpet that covered slick pallets of limestone just beneath the water’s surface.

After gathering their field tools, including snorkels and masks, underwater flashlights, nets, a malleable clasp cant hook, and a backpack full of empty plastic bottles, the scientists stepped into the water, one at a time, to continue their search for the elusive Eastern Hellbender.

Jim Godwin, aquatic zoologist with the Auburn University Museum of Natural History’s Alabama Natural Heritage Program, collected water samples hoping they would contain Hellbender environmental DNA, or eDNA, which is DNA collected from a source other than the actual organism, in this case, the water.

Butler Creek presents an ideal Hellbender habitat, and undaunted by more than a year’s worth of searching with no results, Godwin and his team of scientists waded confidently into the waist-deep waters of the creek. So accustomed were they to the work at hand, they hardly noticed the rocks in their shoes, the occasional leech on their skin, or the stray dog that swam up to investigate the activity as they dived into the water over and over again, blindly running their hands beneath rocks, hoping to feel the large flat body and lose folds of skin indicative of a Hellbender.

“Hellbenders make their homes beneath the large flat rocks in the streams, and their flat and depressed body shape allows them to crawl under these rocks and create little chambers under there, these dens where the adults will remain during the day, and then at night they come out and forage in the streams,” said Godwin. “The males also breed under the large flat rocks in late August and September. The females come to the males and lay eggs that the males then fertilize. The eggs adhere to the underside of the large flat rocks, and a male may breed with several females. The male maintains the brood chamber. He incubates the eggs by waving the loose flaps of skin down the side of his body, which helps circulate water and keep clean water flowing through the brood chamber to aerate and promote development of the eggs.”

Godwin moved upstream ahead of the group to collect water samples. The empty plastic bottles in his backpack would be full of water samples by the time he left Butler Creek, making his work more burdensome as the hours passed.

Godwin collected the samples with hope that they would contain Hellbender environmental DNA, or eDNA, which is DNA collected from a source other than the actual organism, in this case, the water. The eDNA can result from a number of possibilities, including Hellbender mucus, shedding skin, feces, or even carcasses.

“I am a field biologist,” said Godwin, “and there is still this child inside of me that likes to catch things. When you can’t catch it, it is very frustrating – to go out day after day and not be able to find it is very frustrating. The good news is, the eDNA can help us to locate the species without actually capturing it.”

By collecting water facing upstream, Godwin was able to avoid mixing human eDNA into the bottle, thus capturing the cleanest sample possible. He labeled each sample and noted the exact collection location in a journal.

“Hey Jim, someone’s coming,” said Eric Soehren, a biologist with the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources State Lands Division.

“The good news is, he doesn’t have a gun,” said Godwin, as he turned to acknowledge an elderly man and a child walking along a limestone outcrop along the edge of the creek, making their way toward the group of scientists in the water.

Garner recognized the man as the property owner, Ulva Rhodes, whom everyone calls “Uvie,” and his grandson, Dalton.

“It’s just me!” called Garner.

A wave of recognition passed over Uvie, and the men settled into a long conversation about family, fishing, and the work the scientists were conducting in Butler Creek.

“Oh, yeah,” said Uvie, “I’ve seen them. What did you say they are called?”

Among locals, “Hellbender” is one of the least common names used for the massive salamander, preferring instead monikers like “Snot Otter,” “Devil Dog,” “Lasagna Lizard,” “Grampus,” or “Mud Cat,” among others.

“Local landowners and residents can be a good source of information because they live in the area and see the streams and how they change year-round,” explained Godwin. “Those that are out fishing or doing some other outside activity on the water will have accumulated more information about the stream or the area than we can in our short visits. In talking with local residents, we often find that they are quite interested to know what we are doing and why, because we may be telling them something about the life in the streams that they did not know. All in all, we appreciate a good exchange of information with the locals.”

Encouraged by the news that Hellbenders had been seen in the creek, the scientists continued their search, focusing their efforts on one area that appeared promising due to several large underwater rocks, prime habitat for the Hellbender.

“I’ve got one!” shouted Soehren.

The group moved cautiously toward Soehren to avoid clouding the water with silt and debris from the creek bed. Then, one by one, the scientists took turns diving under water, flashlights in hand, to capture a glimpse of the Hellbender hiding in the back corner of a rock cavity.

“They are here!” said Godwin, giving everyone a thumbs up as he emerged from inspecting the Hellbender under water. “We haven’t lost them all!”

Pictured is team leader Jim Godwin (right), an aquatic zoologist with the Auburn University Museum of Natural History’s Alabama Natural Heritage Program, with Duston Duffie (left), a biologist with the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources State Lands Division, and Ben Wilson (center), an undergraduate student in biology at the University of North Alabama.

The Hellbender was just out of arm’s reach, so the team explored other options for extracting the animal from its hiding place. The rock was large and heavy, and they feared if they lifted it using the malleable clasp cant hook, they might accidently drop the rock on top of the Hellbender and kill it.

In addition, moving a rock that large would stir up a lot of silt, and Hellbenders depend on clean, clear water because they absorb oxygen in the water through their wrinkled, baggy skin. Cloudy, silted water would mean less oxygen for the Hellbender, which could put the animal’s life at risk.

Soehren and Godwin both tried to coax the Hellbender out of hiding using a long thin stick, but to no avail.

Knowing Hellbenders are most active at night when they are hunting for food, the scientists asked Uvie if they could return in early evening and try again.

“Sure,” said Uvie. “As long as you aren’t drinking or drugging, you are welcome to come back and work as long as you want.”

Godwin’s team was unable to find the Hellbender when they returned that evening.

Long after sunset, Godwin’s work continued by the light of a headlamp as he ran his water samples through a filter to extract the eDNA. By the end of the expedition, he had collected more than 100 eDNA samples that were sent to a lab for evaluation. It will take several months to receive the lab results that will tell him whether Hellbender eDNA was present in the water.

The scientists spent a week exploring other locations in the area. They canoed more than 8 miles down Sugar Creek and identified Wood Ducks and Great Blue Herons, River Cooters and hummingbirds. The team saw all manner of spiders and fishes, and countless wildflowers in bloom, but no Hellbenders.

“One of the reasons natural history museums and research collections are important is because it gives us a view into the history of the way things were,” said Godwin. “We have records from aquatic biologists indicating a peak in Hellbender captures in the 1960s. From those records, we can ascertain that the Hellbender has been in decline in Alabama since the 1960s and 70s. Declines of freshwater muscles have also been reported during this same period. As scientists, we ask why. What has brought about this decline?”

By the end of the expedition, Jim Godwin, aquatic zoologist with the Auburn University Museum of Natural History’s Alabama Natural Heritage Program, had filtered and collected more than 100 environmental DNA samples that were sent to a lab for evaluation.

Godwin said based on observations, scientists believe the disappearance of Hellbenders, as well as other freshwater species, may be directly related to a decline in water quality.

“We know that we used to have a nice intact forest with good leaf litter on the forest floor that would capture rain water and serve as a water filter, cleaning out debris like sand, silt, clay and other materials before slowly releasing the water into the streams,” said Godwin. “Hellbenders thrive in clean, cool streams, and a natural forest would both clean the water and keep the water cool by providing shade. As the forests are being cut, as the landscapes are changing, as there are more impacts upon the natural areas surrounding the creeks, more soil is being freed up and washed into the creeks with each rain event. The adults living under large flat rocks cannot survive if there is too much soil, sediment and silt coming into the stream system.

“It’s also going to impact the eggs and the larvae, which also need clean water. The Hellbender larvae live in spaces between smaller rocks, the gravel and cobble of stream beds. When these spaces fill in with sediment, there is no place for the Hellbender larvae to live and survive. They are going to be exposed to predation.

“Their food base could also be impacted by the silt. Many species of crayfish, a primary food source for Hellbenders, also depend on clean water to survive. So we see that a natural forest is crucial to Hellbender survival and maintaining a healthy ecosystem.”

Godwin said another cause of the Hellbender’s decline in Alabama is the construction of dams in the Tennessee River, which have changed water flow characteristics, including the creation of lakes where there were once small streams.

“Other factors that are less easy to identify could be chemicals coming in where we have the removal of the forest and it’s replaced with agriculture,” said Godwin. “Of course agricultural land is going to be a source of sediment coming into the stream systems, but we also have chemicals that are being applied to the crops - herbicides, pesticides, insecticides – flowing into the streams. The chemicals may have detrimental physiological effects on the Hellbenders.

“All these things begin to add up and we begin to have extirpations and fragmentations of local Hellbender populations. We also see reduced numbers of Hellbender food sources, like crayfish and fish, so it becomes a loss-of-species snowball effect.”

Out of approximately 836 total aquatic species in the state of Alabama, 246 are imperiled. The outlook for the southeastern U.S., an international hotbed of aquatic diversity, is just as dim, with approximately 763 imperiled aquatic species in the region. It is the threat of losing more biodiversity that pushes Godwin to continue.

“The Hellbender is important because it is an indicator of water quality,” said Godwin. “Where we find the Hellbender we find a stream of good water quality. We have other indicators as well, like fish, muscles and crayfish. When certain species become difficult to find or go extinct, it should alarm us because we know that we are losing water quality.

“Water quality isn’t just important for these freshwater animals, it’s also important for humans. Every living thing on earth relies on water, and we no longer live in a time where we can go out to a stream and just dip up the water and drink it. Our drinking water has to be treated, which has costs associated with it. If we could find ways to bring about improvements in our streams so that we have the natural ecological filtering systems back in place, it would improve water quality for the Hellbender, it would improve water quality for the mussels, the fish, the insects, the crayfish, and it would improve water quality for us. The need for good water quality links us all together. So, for our own good, we need to think about why we are losing Hellbenders, look for solutions and implement those solutions.”

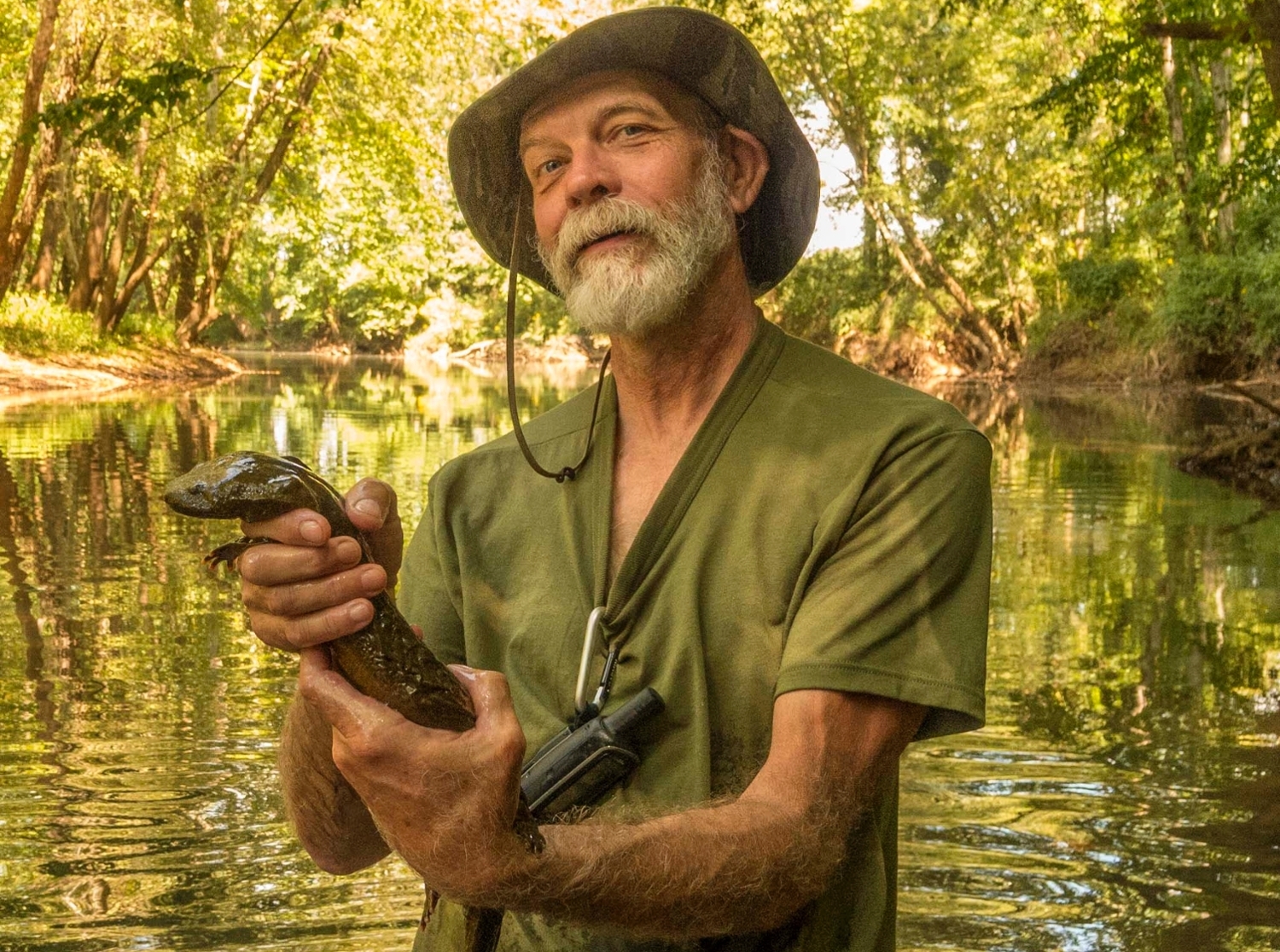

Jim Godwin, aquatic zoologist with the Auburn University Museum of Natural History’s Alabama Natural Heritage Program, poses with one of only two Eastern Hellbenders he has found in Alabama in the last two years.

Godwin grew up in Newport, Arkansas, where he regularly captured animals in a slough that ran through the small town. He has worked with the Alabama Natural Heritage Program for 24 years, and during that span, he has conducted research on a number of declining species in the state of Alabama, including Eastern Indigo Snakes, Alabama Red-bellied Turtles, Alligator Snapping Turtles, Northern Map Turtles, Red Hills Salamanders, and more.

His current work with Eastern Hellbenders is supported in part by funding from the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources and a multi-state grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Assisting Godwin on the Hellbender expedition in August 2016 were the following scientists: Jeff Garner, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries; Eric Soehren, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources State Lands Division and manager of the Wehle Nature Center; Duston Duffie, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources State Lands Division; Ben Wilson, undergraduate student at the University of North Alabama; Mercedes Bartkovich, wildlife consultant with the Wetland Environmental Land Projects; and Scott Rush, assistant professor of Wildlife Fisheries and Aquaculture at Mississippi State University.

Latest Headlines

-

04/23/2024

-

04/18/2024

-

04/18/2024

-

04/18/2024

-

04/17/2024