Auburn Professor Co-Authors Publication on Sexual Dimorphism in Birds

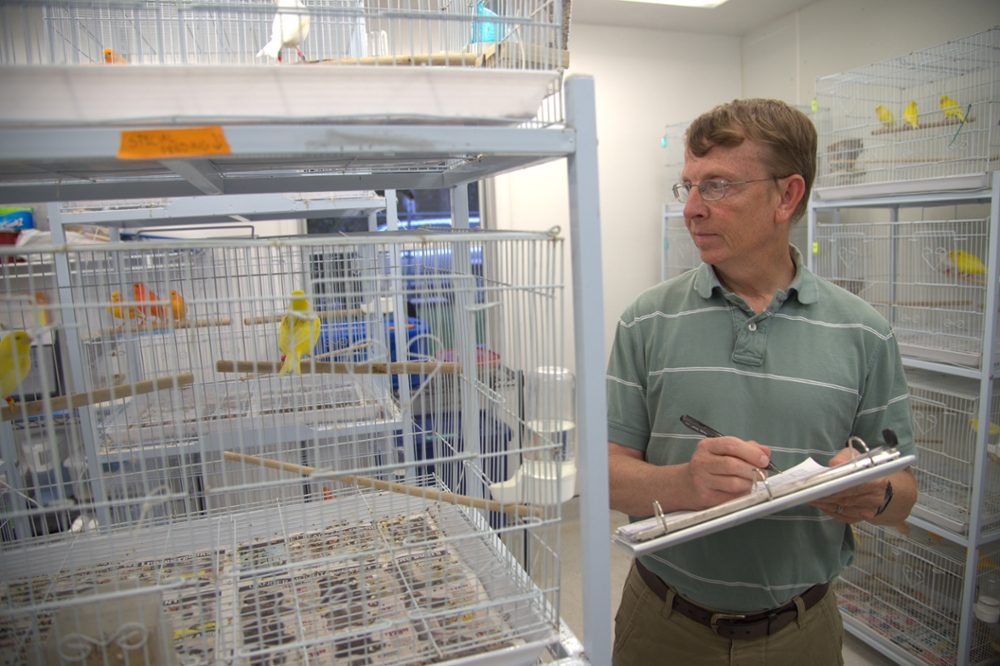

For the last five years, the lab group of Geoffrey Hill, biological sciences professor and curator of birds, has been collaborating with the Miguel Carneiro lab at the University of Porto in Porto, Portugal, and the Joe Corbo lab at Washington University in St. Louis to study different breeds of the domestic canary as a model system for finding the genes that underlie the different plumage coloration and patterns displayed by different canary breeds.

The team has recently made a new discovery through their research which has been published as a cover article in the scientific journal, “Science.” This investigation focused on sexual dichromatism, which is a difference in the coloration of males and females. The paper, which is titled “A genetic mechanism for sexual dichromatism in birds,” describes how changes in the expression of a single gene can generate dramatic differences in coloration between male and female birds.

“The genetic basis for male and female differences is a fascinating topic,” Hill said. “In some bird species, males and females appear so different that they were originally classified as different species. Until our study, we could only speculate on what sorts of genes could cause males and females to have different plumage coloration.”

The canaries that formed the basis for this study were a breed of red canaries. These red canaries were produced years ago when yellow canaries were crossed with a red finch from South America, the red siskin. The resulting offspring captured a gene that enabled them to produce red feathers, with the males having a brighter hue.

Most red canaries were bred to be monochromatic, with males and females both brightly colored, but in one breed, the mosaic canary, sexual dichromatism was selected, making this the only canary breed with distinctly difference male and female coloration. The researchers correctly predicted that with many years of selective breeding, the DNA of mosaic canaries would be of yellow canary origin with the exception of genes responsible for creating differences in coloration between males and females. The scientists found a single strongly divergent region in the DNA of mosaic canaries compared to other canary breeds. This region of differentiation was right next to a key color-controlling genes, Beta-Carotene Oxygenase 2 (BCO2). The authors speculated that the differentiated region controls sex-specific production of BCO2.

Hill said the team expected genes for sex-specific traits to be on sex chromosomes, but the gene for sexual dichromatism that they discovered was not.

“It was on an autosome, so the same in males and females,” Hill explained. “We have to presume that other sex-linked genes, probably genes that control hormone release, interact with our dichromatism gene to cause the different appearances of males and females.”

The scientists tested whether their discovery was specific to canaries by studying the patterns of gene expression in other finches. The same mechanism discovered in canaries was found to work in other finches as well.

Hill added that the group plans to continue their research together.

“The genetic basis for different morphologies of males and females is a very fundamental discovery,” he said. “This particular study focused on plumage coloration in birds, but it provides a foundation for studies of other dimorphic traits, including in humans.”

Latest Headlines

-

07/09/2024

-

Summer Bridge Program celebrates 21 incoming Auburn students as they prepare for future STEM careers07/02/2024

-

07/02/2024

-

06/17/2024

-

06/07/2024