Clamping down on crocs in Costa Rica

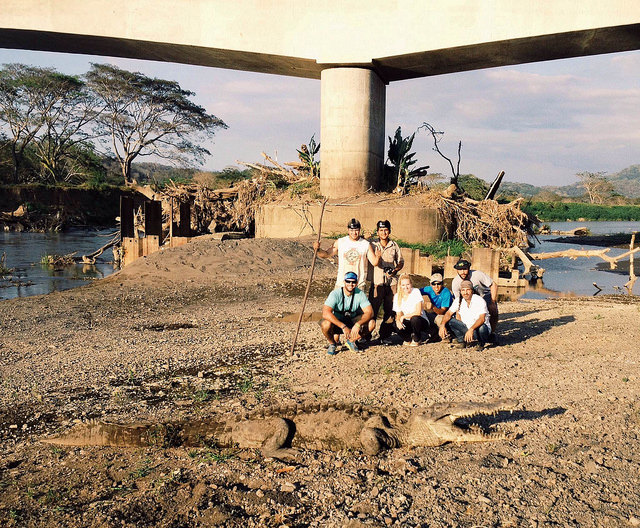

An Auburn graduate student and former "Gator Boy" who wrestled with alligators in Eufaula continues his research in Costa Rica; this time, with crocodiles.

"In terms of behavior, crocodiles seem to be a lot gnarlier than alligators," said Chris Murray, a member of the Craig Guyer lab in the Department of Biological Sciences at Auburn University, who is investigating the physiological and ecological factors that affect crocodilians within that country. "They're larger, and don't tire out nearly as fast, if ever, in some instances. They have a lot of fight and they're more nimble and flexible than your average alligator."

He is seeking solutions for crocodile population issues identified by a Costa Rican commission that studies the animals.

"What they've found recently is that there is a male bias in sex ratio, so some of their data suggests that there are too many males per female," Murray said. "There has also seemingly been an increase in attacks throughout the past few years."

Murray and his team, field technician Mike Easter of Animal Planet's television show "Gator Boys," staff of the Palo Verde Biological Research Center, Mahmood Sasa and Sergio Padilla, and others, are working to find potential management implications to combat the problem.

The team is testing hypotheses that examine why there may be an abundance of males. Some data suggests regional warming may play a role in nest temperatures and sex determination in the eggs, or the potential presence of ecotoxins within the system.

The Palo Verde Biological Research Station, where the team is based, is located in the Guanacaste Province of Costa Rica, near the Pacific Coast, and inside the Palo Verde National Park.

"We're surveying local populations near the Tempisque and Tarcoles rivers and working with a lot of folks there to find out as much as we can," said Murray. "Members of our collaborative team are doing a lot of blood chemistry and sampling to look at glucose, stress, hematocrit and other physiological factors."

Murray's ultimate goal is to mediate the conflict between humans and crocodiles by gathering enough data to make an informed, biologically accurate decision on how the system can be relieved of any issues.

Last year, Murray worked with alligators at the Eufaula National Wildlife Refuge exploring physiological differences between sexually and non-sexually active alligators, young versus old alligators and whether there were any seasonal differences. Some of the hypotheses tested in Eufaula are being used in his current research in Costa Rica.

The team's approach to a crocodile capture is dictated by the size of the animal. If the crocodile is considered small, 1.5 meters or less, it will be grabbed by hand directly out of the water. Larger crocodiles require a breakaway, metal snare pole that cinches safely over the snout or neck.

The largest crocodiles call for the top jaw rope method.

"We slip a rope lariat over the top jaw to begin manipulating the crocodile as best we can, before temporarily securing the mouth with more rope and tape," Murray said. "We then move the animal to another safe location where we can process it. We want to make sure the stress is minimal both on us and the animal, most importantly."

After a crocodile has been secured, Murray and his team calm the animal by covering its eyes with a damp towel and then begin collecting data starting with blood. The blood chemistry allows them to look at sex-steroid regimes and stress regimes.

Another important step is marking the animal.

"To mark the animal, we remove scutes in a series of numbers on the tail so that every individual gets its own number," Murray said. "That way, if the crocodile were to be recaptured, we would know the history of that particular croc. Once that's done, we make sure the animal returns to the water quickly."

He said his favorite capture was the most recent, and surprisingly, most uneventful process to date.

"Our last trip down there was incredible," Murray said. "My team worked and communicated efficiently, and the animals were released quickly and stress free. The fact that everything flowed so smoothly is exciting to me."

Murray credits the original Crocodile Hunter for his initial interest in crocodilians.

"My inspiration really came from watching Steve Irwin when I was a kid," Murray said. "That's when I realized I could make a job out of this, so I went down that road, and I'm still on that road today."

Murray plans to graduate with his Ph.D. next year and said he hopes to continue working in Costa Rica for a lifetime.

"It's great to be able to interact with the local researchers," Murray said. "Their research has really laid the groundwork for us to do our work. They're nice enough to allow us down there and hopefully, we can help them out as best we can."

Latest Headlines

-

02/12/2025

-

02/11/2025

-

02/10/2025

-

01/30/2025

-

12/03/2024