Two Alabama authors: Kathryn Tucker Windham of Selma and

Nelle Harper Lee of Monroeville.

In background is Mrs. Windham's daughter, Helen Ann (Dilcy) Hilley of

Birmingham

and Alabama folk artist Charlie Lucas of Selma. Miss Lee is a

past Alabama

Academy of Honor inductee.

Montgomery

Advertiser

Aug. 19, 2003

AL BENN'S ALABAMA

State's best lauded

By Al Benn

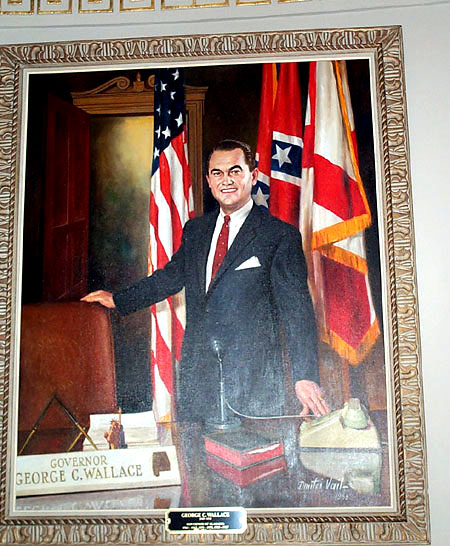

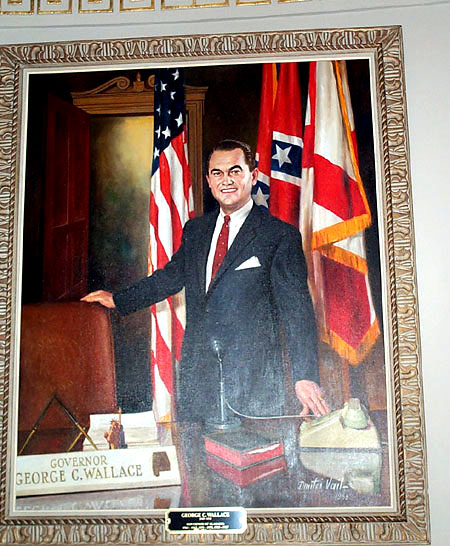

When George Wallace was

running for governor and president -- often at the

same time -- he liked to say

at rallies that Alabamians were "as refined

and cultured" as anyone in the

country.

He also enjoyed calling those

of us who covered his campaigns

"pointy-headed" pencil pushers

with preconceived, jaundiced views of

Alabama.

Wallace knew he was playing to

the crowds that turned out for his campaign

speeches, but he also was

aware that his comments contained more than a

kernel of truth.

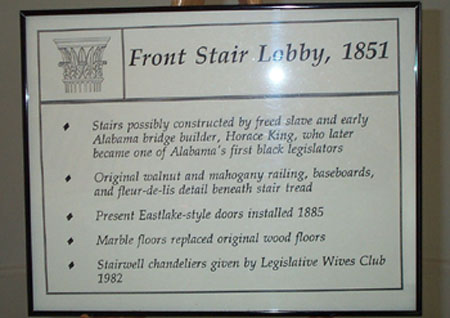

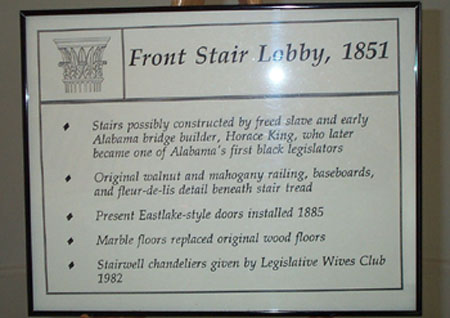

Monday's induction ceremony at

the annual Alabama Academy of Honor

reflected Wallace's belief

that his state has produced some of America's

most important citizens.

The newest inductees are:

(1) Gov. Bob Riley: A

successful businessman who served three terms in

Congress before being elected

to Alabama's most important position last

year.

(2) Don Logan: As chairman of

AOL Time Warner's Media and Communications

Group, he oversees one of the

world's largest print and electronic

operations.

(3) Malcolm Portera: As

chancellor of the University of Alabama System, he

supervises the state's largest

higher education enterprise with a $2

billion budget, 42,000

students and 21,900 employees.

(4) Van Richey: President and

chief executive officer of American Cast

Iron Pipe Co., he guides a

business that has been named by Fortune

magazine as one of the 100

best companies to work for in America.

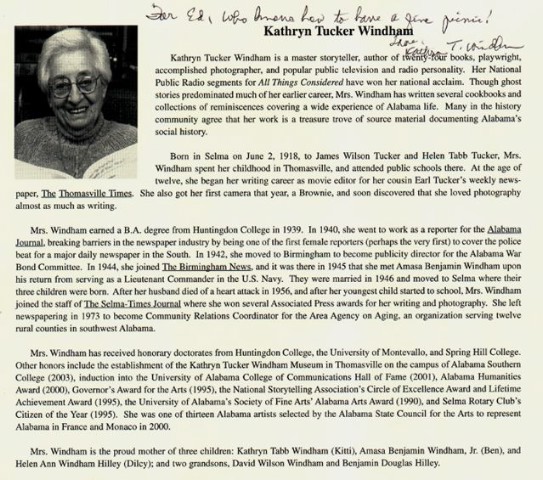

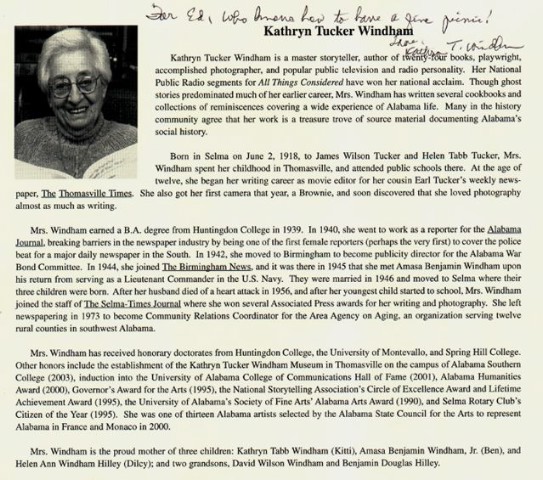

(5) Kathryn Tucker Windham:

She has established herself as a nationally

known storyteller, author,

radio personality and photographer.

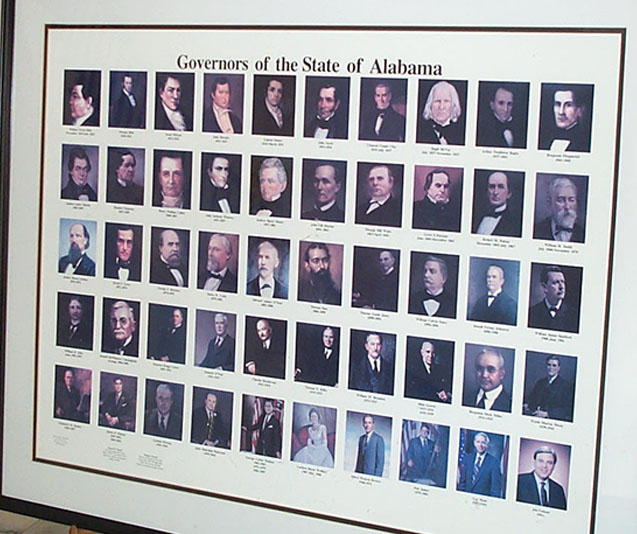

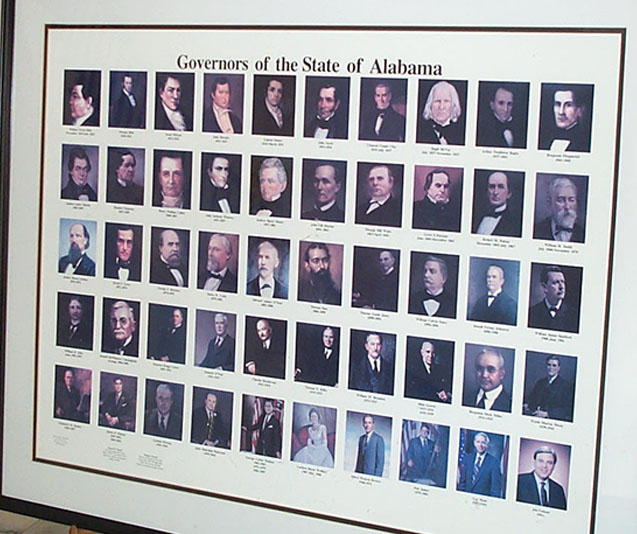

The five joined an illustrious

group of Alabamians who preceded them in

induction ceremonies dating

back to the academy's inception in 1965.

Many of those honored in the

past were on hand to welcome the newest

group. Among them was Nelle

Harper Lee, famed author of "To Kill A

Mockingbird." She watched

quietly from the balcony.

"This is an academy of

achievers, deep thinkers and dreamers" said

Portera, who spoke for the

newest group of inductees.

Riley, who flew in from

Mobile, was a few minutes late and he hurried into

the big room at the Capitol to

rousing applause as he slipped into his

jacket.

The governor spoke for a few

minutes about his favorite subject -- moving

Alabama forward. His comments

echoed what he's been saying on the tax

reform stump over the past few

weeks, but he didn't dwell on that.

"You are the best of Alabama,"

he told current and past inductees.

My Yankee relatives and

friends have, at times, taken a dim view of

Alabama, and I try my best to

set them straight. It hasn't been that

difficult, not with the likes

of those who are members of the Academy of

Honor.

Lee is one of the world's most

celebrated authors. Wernher von Braun and

his team of scientists

developed the rocket that put Americans on the

moon. Paul Bryant led the

University of Alabama back to gridiron

greatness. Thomas Moorer once

was chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Condoleezza Rice is one of our

president's most trusted advisers.

Add to those achievers dozens

of industrialists, businessmen, jurists,

journalists and political

leaders and it's quite a lineup of excellence --

one that should make all

Alabamians proud.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alvin Benn writes a column for

the Montgomery Advertiser. If you have a

column idea, write, or call

his home, (334) 875-3249.

Nelle Harper Lee signs copy of her book, "To Kill a

Mockingbird" for Ben Windham,

Editorial editor of The Tuscaloosa News, and son of Kathryn Tucker

Windham.

BEN WINDHAM: An

encounter with Harper Lee

The Tuscaloosa News

Aug. 24, 2003

There was interesting news in the telephone call from Selma. My mother,

author-storyteller-photographer Kathryn Tucker Windham, would be

inducted in a few days into the Alabama Academy of Honor.

The Legislature created the academy in 1965 to honor the 100 greatest

living Alabamians. Needless to say, I was one proud son.

I’d known for some time that my mother had been selected. The news was

that Harper Lee, who nominated my mother, might attend the ceremony in

the old House chambers in Montgomery.

A public appearance by Harper Lee anywhere is news.

Her 1960 novel “To Kill a Mockingbird" is one of the most widely read

books on the planet, selling more than 30 million copies in English and

translations in three dozen languages.

It won the Pulitzer Prize and was made into a classic movie, starring

Gregory Peck in the role of a lifetime.

But for all of the stunning success of her book, Lee, who turned 77 in

April, has kept a low profile. Some people call her a recluse; others

say she simply enjoys her privacy, sharing her life with a small circle

of family and friends.

In the Alabama vernacular, she likes to keep her business down home.

She has not granted an interview since 1964. Except for one event in

the 1980s, she has not spoken in public for years.

According to reports, she divides her time between her small south

Alabama hometown, Monroeville, and New York City, where she walks the

streets happily incognito, dressed down like a native.

Even in Monroeville she seems to begrudge her celebrity. She has never

attended a local performance of the play adapted from her novel in

which townspeople portray the characters. Years ago she stopped signing

her books for Monroeville stores when she learned the prices were being

jacked up by merchants and customers alike.

She sticks tightly to a small circle of family and friends. Wary of

fans and reporters, she does not enjoy being photographed.

As soon as I heard she might be in Montgomery last Monday for the

Academy of Honor induction, I called my younger sister.

“How gauche would it be if I took a copy of 'To Kill a

Mockingbird’ for her to autograph?" I asked.

My sister didn’t answer quickly. It would be our mother’s day to shine,

after all.

“Well," she said finally, “I don’t think it would be too tacky. I have

an autographed copy. I think you should have one, too."

The answer didn’t sound all that convincing.

“OK," I said. “I don’t really want to bother Miss Lee. I’ll think about

it."

I thought until last Saturday, when I decided to go ahead and be

gauche. I’d read that Lee is polite, but a friend also said she has

“hell and pepper in her." I figured if she didn’t want to sign, she

would say so.

The only problem was, I couldn’t lay hands on my copy of her famous

book.

We recently introduced a massive new entertainment center into the

great room of our house, displacing novels, records, tapes and

electronic gear. We haven’t quite gotten things straightened out yet,

and books, towering in precarious piles, still clog the area around the

coffee table.

Searching for “Mockingbird," I waded into the thick of this literary

logjam, pulling out volumes I hadn’t seen in years: a biography of John

Lee Hooker, a collection of Chekhov’s works, Archibald Rutledge’s

wonderfully anachronistic portrait of a vanished South, “God’s

Children."

But Lee’s masterpiece remained as elusive as its author.

Then I remembered. I had loaned it to my son, who had the book on his

ninth-grade reading list last year.

“Oh yeah," he said when I pressed the issue. “I think I still have it

... somewhere."

Again, it was not a reassuring answer. By early Sunday afternoon the

book still hadn’t turned up.

Only 20 hours remained until the Academy of Honor induction. I prepared

to head out for one of Tuscaloosa’s two bookstores that do business on

Sunday.

I was tying my shoes when he burst in triumphantly.

“Found it, Dad!"

And so he had ó or most of it. The dust jacket was missing, and

the cover bore scars of public school classrooms. Inside the front

cover, in large block letters, he had written his name with a black

Magic Marker.

It was not the kind of thing to present to an eminent author. I decided

to look for a more presentable copy.

I couldn’t find one. The stores had paperback copies of “To Kill a

Mockingbird," but if I wanted a hardbound copy, it would be a special

order.

That wasn’t an option, and presenting a paperback for Lee’s inscription

offended even my sense of decorum.

Deflated, I decided to forget about seeking an autograph and just enjoy

the ceremony with my family.

It was only at the last moment ó as I headed out the door early

Monday for Montgomery ó that I decided to grab the old hardback

copy anyway. Just in case.

I met up with my younger sister at her home in Birmingham.

“What do you think?" I asked, showing her the scarred, jacketless,

written-in book.

“I think it’s fine," she said. “Look what I’m taking."

It was a huge poster for the movie of “To Kill a Mockingbird."

Apparently it had been collected from some Spanish-language cinema. A

portrait of Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch dominated the poster, under a

banner that read “Para Matar un Sinsonte."

“The English-language posters for ëTo Kill a Mockingbird’ are

pretty hot," my sister explained. A friend had given her the more

easily available Spanish one.

I didn’t feel nearly so awkward then.

Privately, I doubted that Lee would give either of us an autograph, but

I had pretty much convinced myself that it didn’t really matter. It

would be much more interesting, I thought, if we could talk to Lee

about her life and literary career.

What little I knew about her current activities I gleaned from an

article by a writer named Marja Mills that was published last September

in the Chicago Tribune. Lee wouldn’t be interviewed, but Mills managed

to talk to her sister, some of her friends, a Monroeville minister and

others to put together an interesting portrait.

It said, among other things, that Lee is a Republican, a conservative

on some issues and liberal on others. One of her friends said she is

frustrated that the world has grown “coarse and obscene" and that the

South has failed to come to grips with racism.

Why she has never published another book is a question that has

fascinated her fans and critics for years. Alice Finch Lee explained to

Mills that her sister had simply “hit the pinnacle" with her first

novel and there was no need to try to top it.

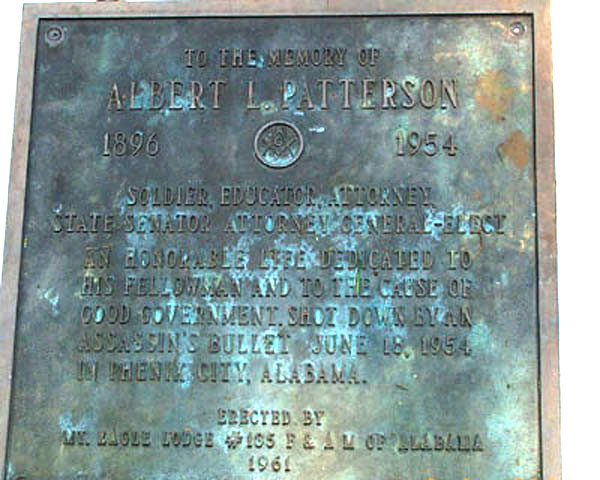

I’ve heard alternate explanations. Years ago, I met Archulus Persons,

Truman Capote’s father (Capote took the surname of his Cuban stepfather

after his mother remarried). By blood, Truman was related to the

Alabama family that includes Gordon Persons, the governor who brought

Coach Ralph “Shug" Jordan to Auburn and martial law to Phenix City when

Attorney General-elect Albert Patterson was murdered.

Arch Persons didn’t say so, but he and his wife weren’t very good

parents during their troubled marriage. Truman was reared mostly by

female relatives in Monroeville. Their house happened to be next to

Harper Lee’s; Lee and Capote grew up together and remained firm friends.

What Persons did tell me was that Capote wrote “almost all" of “To Kill

a Mockingbird."

I don’t believe it, especially coming from Persons, who struck me as a

blowhard. Moreover, Lee’s sister adamantly denied the same allegation

in the Chicago Tribune piece, calling it “the biggest lie ever told."

Perhaps Capote helped here and there with her novel, just as Lee helped

him during his research for “In Cold Blood." But I believe “To Kill a

Mockingbird" is very much Lee’s own work. The similarities to Capote’s

own pieces set in Alabama are no more than one would expect from great

artists who shared a childhood together, talking about people, ideas

and stories.

I figured Lee would never talk to me about Capote, but I figured there

would be plenty of other things to discuss.

We share a lot of mutual interests. She is a devoted follower of

Alabama football. Like me, she had a father whose given name was Amasa.

She enjoys fishing, local history and down-home foods. Eudora Welty,

Mark Twain and William Faulkner are among our favorite writers.

My sister and I got to Montgomery in time for a reception before the

induction ceremony. I gave my mother a kiss and a bear hug. Then I

couldn’t help myself. I asked her if Harper Lee had come.

“She’s right there," my mother said, gesturing toward a coffee table

near a corner.

I couldn’t have picked her out. She was short, gray-haired,

bespectacled and smiling. She wore a blouse with pleasing patterns of

crimson and white.

Furthermore, she didn’t shy away when I asked for an autograph ó

for my son, I explained, proffering the battered book. She graciously

agreed at once.

There was no room on the coffee table, so she suggested using my back

as a substitute. I stooped over, she placed the book firmly between my

shoulder blades and signed it.

I pressed my luck. “May I have a photo of you and my mother?" I asked.

Again, she readily agreed. As I aimed in their direction and fumbled

with the digital knobs, a swarm of other cameras erupted from nearby

coats and bags and flashes fired off from every direction. Lee did not

seem particularly pleased.

Realizing that it was not a good time to try to start a conversation, I

thanked her and wandered off with my book to find my sister.

She stared at the inscription.

“Oh, I hate you," she said. “Do you think she’ll sign my poster now?"

“Only one way to find out," I replied.

Again, Lee agreed. But her patience clearly had worn thin. A friend

trying to photograph her in the act of autographing the poster got a

waggling finger signifying “no" from the author.

It was at that point that my old friend and colleague Alvin Benn, now

retired as a reporter from the Montgomery Advertiser, cruised up.

Al is no shrinking daisy and he doesn’t live life in kid gloves. You

know when Al’s in the house.

“Harper Lee!" he exclaimed.

Evidently they’d crossed paths before.

“You’re retired," she said, heading out of the reception room. Then she

added with a smile, “You bastard."

Their exchange was loud enough for everyone to hear but Al took it in

stride. Laughing, he said he might use Lee’s comment on the dust jacket

of a book he’s writing about his life and times in the news business.

My mouth was open. I decided the hell and pepper had temporarily taken

precedence over the part that finds the world crude and obscene.

Al saw it as kind of an affectionate salute.

“Besides," he told me later, “it’s not every day that a world-famous

author calls you a bastard."

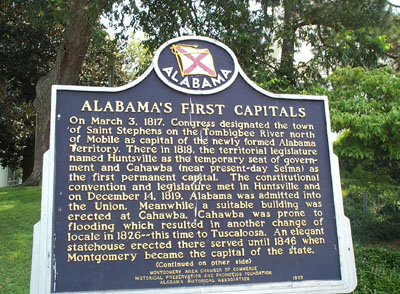

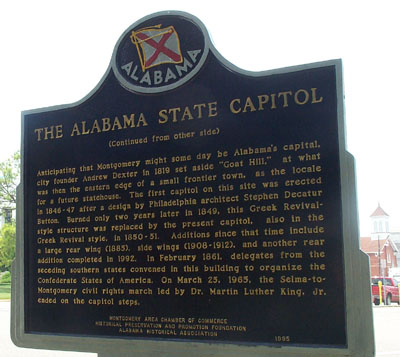

Soon we were summoned to the induction ceremony in the old House

chambers.

Unlike other members of the academy, who took their seats on the floor

in comfortable antique chairs, Lee sat in the balcony, where the press

corps had covered the lower chamber when the old Capitol was still used

by the Legislature.

Afterward, she attended a luncheon for the honorees but she was seated

at another table, in a decidedly inconspicuous position against the

wall.

Our table was slow to leave. People kept dropping by to talk to my

mother. By the time I looked around, Lee was gone.

Still, it hadn’t been a bad day. I was full of pride for my mother’s

honor. And I could one-up Alvin Benn. How many people can say they had

a great American author autograph a classic book squarely between their

shoulder blades?

The next day, a friend e-mailed me a photo he snapped of Lee using my

back as a writing desk. But “don’t forward it to anybody," he warned in

the e-mail. “I don’t think Miss Lee likes that kind of thing."

Don’t worry, cuz. I’ll keep it down home.

Reach Editorial Editor Ben Windham at (205) 722-0193 or by e-mail at

ben.windham@tuscaloosanews.com

Harper Lee signs movie poster for Dilcy Windham Hilley.

Looking on are Kathryn Windham's grandson,

Ben Hilley, a seventh grader at Pizitz Middle School in Birmingham;

Kathryn Windham; and Dilcy Windham Hilley.

Alabama Academy of Honor inductee Don Logan,

chairman of Time Warner's Media and Communications Group.

Past Alabama Academy of Honor inductee is former Gov. Don

Siegelman.

Past inductees, from left, are former University of Alabama president

Dr. Joab Thomas and former Auburn University president Dr. Harry

Philpott,

and Mrs. Thomas.

Past inductee is former Gov. John Patterson, left.

Patterson chats with former Secretary of State Jim Bennett

From left: Nelle Harper Lee and Dot Stewart, both of

Monroeville,

and Josey Ayers, The Anniston Star, Anniston, Ala.

Gov. Bob Riley is inducted to Alabama Academy of Honor. Looking

on are Thomas N. Carruthers

and Judge C.C. "Bo" Torbert Jr.

State Archivist Ed Bridges, Administrative Liaison for the Alabama

Department of

Archives and History; past academy inductee Dr. David G. Bronner of the

State

Retirement Systems; and Barrett C. Shelton Jr. a past inductee, and

publisher of

The Decatur Daily in Decatur, Ala.

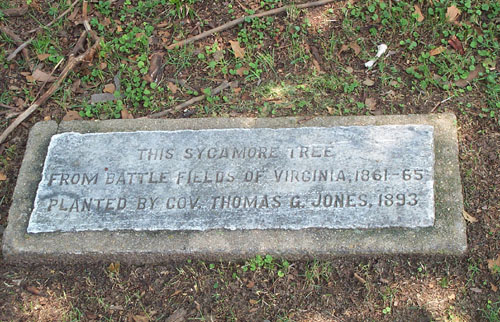

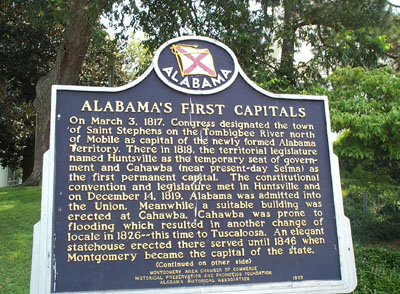

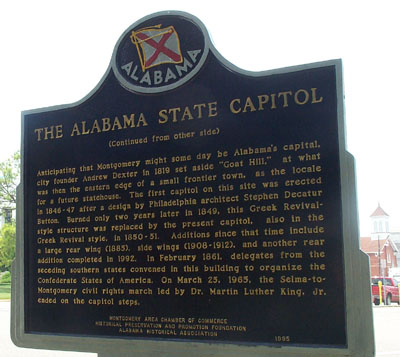

A walk through the Capitol and grounds

after the Academy of Honor ceremony...

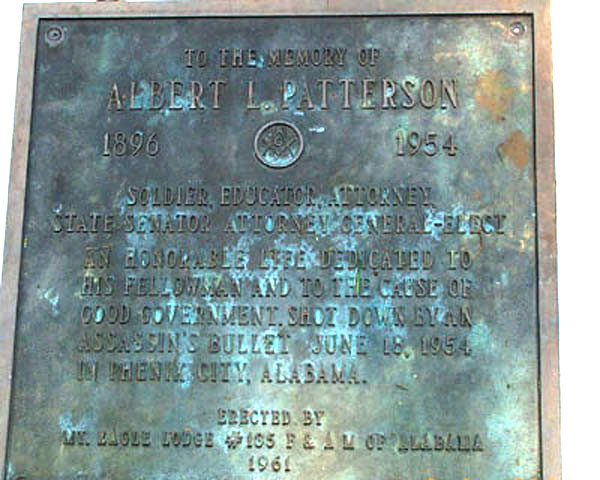

Statue of former Gov.

Albert Patterson.

Finally, the best part ...

Lunch

at Chris' Hot Dog Stand, Dexter Avenue

Joyce Bodiford prepares one of Chris' famous hot dogs "all the

way," while owner Theo Katechis looks on.

Behind Katechis is employee Greg Cumuze.

Odd-Egg Editor

By Kathryn Tucker Windham

This eye-opening memoir by a

far-minded and engaging writer recalls what life was like for a female

reporter in that unbudging male bastion, the southern newsroom.

Chapter 3

Recollections of Chris’s Hot Dog

Stand

Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama

In the days before Pearl Harbor

I was still covering the police beat, still leaving with Mr. And Mrs.

Allen Woodall and their two little boys, Sonny and Buddy, at 28

Cloverdale Park (I paid forty dollars a month for a room with private

bath, maid service and two meals a day), and still being paid fifteen

dollars a week. I was making small weekly payments on a Schwinn

bicycle and an Underwood portable typewriter. They,

and a few books, constituted my worldly possessions.

My recreation budget would have

been extremely limited and I likely would have been broke most of the

time had it not been for my radio movie reviews and the “lamp shade

circuit.”

Allen Woodall, who was

advertising manager for Radio Station WSFA, arranged for me to get

passes to aall the movie theatres in exchange for doing brief weekly

reviews for the station. The experience I had had writing movie

reviews for my cousin Earl’s weekly paper, back when I was in high

school in Thomasville, stood me in good stead.

For the “lamb shade

circuit,” I wrote fluffy articles about small local businesses, such as

specialty shops, tearooms, home furnishings and interior

decorating establishments (hence the name “lamp shade circuit”) and

others. The articles were used on the business review page of the

paper, and I was paid $7.50 weekly for my contributions. This

work was separate and distinct from my job as a reporter and was dune

during my off hours.

Even with my augmented income, I

might have gone hungry at noon occasionally if it had not for for

Chris’s hot dog stand. Chris’s place was on Dexter Avenue,

convenient to the newspaper office, and until the war with its blackout

regulations came along, his big neon sign “Famous Hot Dogs”

illumined the area at night. I patronized Chris’s nearly

every day. At the entrance were racks of cigarettes and candy,

often scarcely filled because of World War II rationing, and a soft

drink box.

Although I cannot now find

anyone who can verify it (as Mark Twin said, “I find that the further

back I go, the better I remember things, whether they happened or

not”), I recall that near the entrance was a device known as a

Pan-o-ram where customers could insrt a dime and see a talking

movie. The machine was a sort of glorified nickelodeon and was

owned or promoted by James Roosevelt, son of the president. It

obviously was never widely popular, and the advent of television marked

its doom.

A long counter with stools

extended down the left side of Chris’s place, and over on the right

side, behind a partition, was a long corridor with booths and small

tables along the walls. The stand was crowded with customers

(white only) during the lunch hour, and Chris seemed to be everywhere –

taking orders, serving food, running the cash register, checking on the

kitchen, greeting customers. “Yes, ma’m. Wudkinidufuhyse

today, ma’m? One hot dog? Two?

Bestindewholewol.” They were.

Chris’s hot dogs were juicy and

tender, served hot on a fresh bun with everything on them, including

his own secret Greek sauce. They cause eight cents each. He

had to sell a lot of hot dogs to support his wife and five children.

Chris, who had come over from

the old country, had a rounding stomach and a swarthy complexion that

made him look as if he needed a shave. He had a scattering

of gold teeth and his black eyes sparkled with friendliness. He

always cashed my check on payday. “Gotta check? How

much, ma’m? What? No grow! No grow! Sometimes I

felt that he lamented the smallness of my salary as much as I did.

Chris was intensely patriotic,

and after the way started, he was always eager for news.

When I walked in, his daily greeting was, “Watzewarnus?

Good? Bad? Wewwhipem yet?!”

After Pearl Harbor, Chris became

even more ardently patriotic. He invested in war bonds and urged

his patrons to do the same, he promoted scrap metal and aluminum

drives, and he displayed flags all over his hot dog stand.

When customers complained of shortages, Chris was prompt to

remind them, “Wegottawinwar!”

The end

Thanks for visiting my

Web

page!

Ed Williams

Auburn University

Auburn, Alabama

From left, Nelle Harper Lee, Kathryn Tucker Windham and Ed Williams