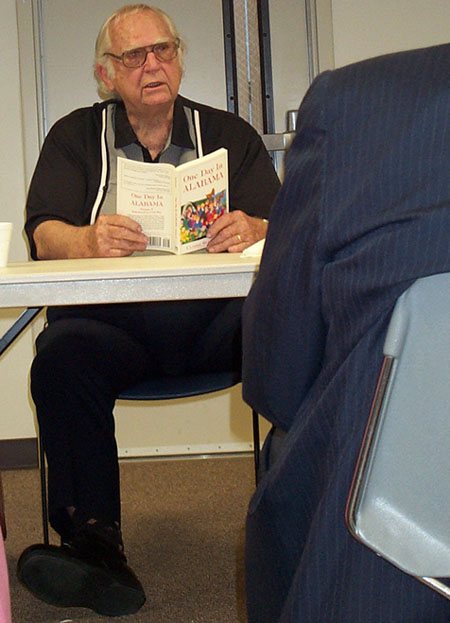

Veteran newspaper man Clarke Stallworth, Birmingham Post-Herald

and The Birmingham News, reads from his book, "One Day in Alabama,"

the story of "Love and Death on the Flaming River," about a steamboat

that caught fire and burned on the Tombigbee River just before the Civil War.

An Afternoon

with Clarke Stallworth

Lee County Historical Society

City

of Auburn Meeting Room

Sunday, Jan. 8, 2006

2:30 p.m.

Clarke

Stallworth

Columnist-Author-Historian

(and occasional

magician)

"I enjoyed Clark

Stallworth's presentation. I taped up one of his "what does this story

mean to the reader" pieces of paper next to my monitor (until it was

defaced to read "why is this story mean to the reader?").

I think it cuts through a lot of the murk of writing to think of what

needs to get in a story. You can leave out what only matters to you and

no one else. Or show them why it does (or should) matter."

--Poynter Online

Sept. 22, 2005

Here from beginning to the end

Clarke Stallworth had byline on first, last editions of Post-Herald

Commentary By CLARKE STALLWORTH

BIRMINGHAM POST-HERALD

I remember that day in 1950, when Jimmy Mills called us all into his office on Third Avenue North.

"Well, folks," he said, "tomorrow is the last edition of The Birmingham Post."

My face must have fallen because Jimmy said, "Don't worry, Clarke, you've still got a job."

Yesterday, about 3 p.m. Birmingham time, I had just finished a workshop for the South Carolina Press Association on coaching writers, and I was sitting in a car outside the press association building in Columbia, S.C.

Don Kausler, editor of the Anderson Independent-Mail, handed me his cell phone. It was Jim Willis, editor of the Birmingham Post-Herald.

"Well, Clarke," Jim said, "tomorrow is the last edition of The Birmingham Post-Herald. I wanted to be the one to tell you."

Jim thanked me for my contribution to the paper these past five years, and I thanked him for giving me one last shot at journalism.

He took me on in 2000, when I was 75 years old. Today, I'm 79 and still working, at least until I finish this piece.

I had a byline on page one of the first edition of the Post-Herald in 1950. And today, I have a byline in the last edition of my newspaper.

That has a nice ring to it, a real sense of closure, of completion, of rounding things out.

I remember coming to the old Post in 1948, a green kid just out of journalism school at the University of North Carolina. I couldn't buy a story at first, working my way up to writing obits from typing up all the sermon topics in town.

Things changed when I got a Speed Graphic camera. We were short of photographers, and I began to get some good assignments.

One of them was to investigate Ku Klux Klan violence, and this led me into an ambush in a store at Sumiton, in Walker County.

Two Klansmen attacked me, and I remember the sound of the hammer as it whistled past my head. But I boarded a handy Greyhound bus and got away.

Later, at a night Klan meeting in Warrior, I remember the bitter taste of fear as I was surrounded by hooded men with rifles and shotguns.

One of them was Robert Chambliss, who later blew up Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killing four little girls. I got out of that one, too.

I covered the Phenix City story in 1954, when a local gangster killed the attorney-general-to-be. I watched Alabama National Guard troops take over the governments of the city and county under martial law and watched soldiers knock down doors looking for gambling equipment.

I covered state government for the Post-Herald in the Folsom, Patterson and Wallace administrations and helped to direct the coverage of the civil rights demonstrations in 1963, when I became city editor of the paper.

Later, I worked for the Columbus, (Ga.) Ledger-Enquirer and The Birmingham News, retiring from The News in 1991.

While I worked for The Birmingham News as city editor and managing editor, I was in the position of battling with my old newspaper, and sometimes it was not very pleasant, competing with old friends.

I seem to have a sort of parallel relationship with the Post-Herald. It lived for 55 years, and I worked on it for a good number of those years. I was a green kid when it was young, and grew into old age alongside it. It was almost like having a newspaper brother.

What I remember, and treasure, most about the Post-Herald, was the people, of course.

I had mentors like Duard LeGrand and Jim Willis. Duard was the best boss anybody ever had, and Jim Willis was my angel, giving me another shot when others might have looked hard at the gray hair.

I worked with Larry Fiquette, who wound up at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and Howell Raines, who ran The New York Times for a while. There was Bill Mobley, the ex-boxer who covered the cops like a champion. And Martin Waldron, a terrific reporter and my worthy opponent for the city editor's job, who became the Southern correspondent for The New York Times.

And there was Jane Aldridge and John Staed and Lillian Foscue and Karl Seitz and Bob Farley and Elaine Witt. The names go on and on, all the people who helped me become what I am.

I am proud to have been present at the birth — and the death — of a first-class newspaper, a newspaper of singular quality, a newspaper that shone like a diamond in the light. And if I contributed even a tiny bit toward that shine of excellence, I am proud of that, too.

The Post-Herald and I have had a good run. For me, our time together has been a joy and a delight.

Thanks for visiting

"An Afternoon

with Clarke Stallworth"

Ed Williams

willik5@auburn.edu

Professor

Department of

Communication

and Journalism

217 Tichenor Hall

Auburn University