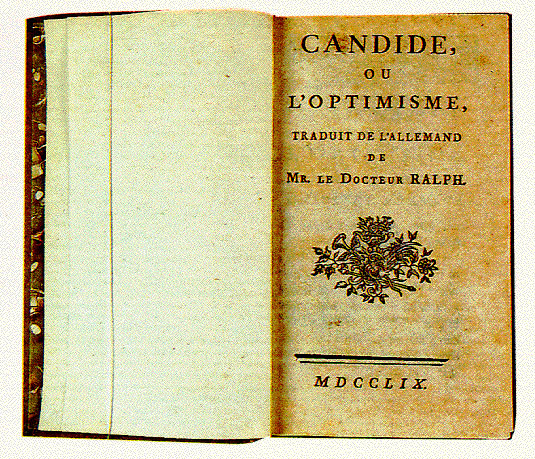

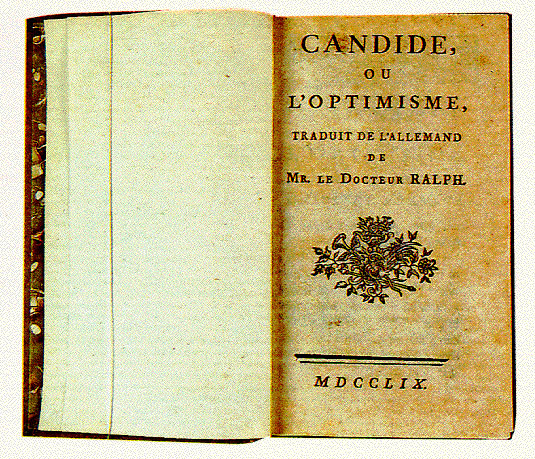

Voltaire's

Candide

|

Voltaire's Candide |

Study

Guide to Voltaire’s Candide

Terms:

Anabaptists:

The term literally means “one who is baptized again.”

Anabaptists rejected what they considered empty rituals of other

Christian groups, particularly infant baptism.

They advocated not only adult baptism but also the central role of a

personal faith in Jesus Christ.

Augustine

(354-430):

Christian Neoplatonist, North African Bishop, Doctor of the Roman

Catholic Church, Augustine developed the doctrines of original sin,

predestination, divine grace, and divine sovereignty that defined both Roman

Catholicism and Protestantism during Voltaire’s day.

Pierre Bayle (1647-1706): French philosopher, critic, and advocate of free and independent thought, Bayle began as a Protestant, converted to Catholicism, returned to Protestantism, and ended as a skeptic. Voltaire viewed Bayle as a leading opponent of optimism and advocate of religious tolerance.

Christianity

(orthodox):

Despite doctrinal divisions, orthodox Christians view God as the

all-good, all-powerful Creator who made his creatures “sufficient to stand but

free to fall.” The Apostle’s

Creed lists the tenets accepted by most orthodox believers: I believe in God, the Father almighty, creator of heaven

and earth. I believe in Jesus Christ, God's only Son, our Lord, who

was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered

under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried; he descended to the dead.

On the third day he rose again; he ascended into heaven, he is seated at the

right hand of the Father, and he will come again to judge the living and

the dead. I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic church, the

communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the

body, and the life everlasting.

conte:

The French term for a prose narrative such as tale or short story,

particularly one involving adventure. Candide is frequently

labeled a “conte.”

Deists:

Voltaire, like many 18th

century thinkers was a Deist. Deists

rejected orthodox Christian teachings, were skeptical of supernatural revelation

or inspired faith, and the concept of revealed truth and argued instead for a

Supreme Being (the clock-maker image whose laws could be understood through

nature and reason.

hyperbole:

Hyperbole is a literary term for an extravagant exaggeration used for serious or

comic purposes. It is one of the tools of the satirist.

irony:

Irony is the discrepancy between what is said and what is meant, what is

said and what is done, what is expected or intended and what happens, what is

meant or said and what others understand. Sometimes irony is classified into

types: in situational irony,

expectations aroused by a situation are reversed; in cosmic

irony or the irony of fate,

misfortune is the result of fate, chance, or God; in dramatic irony. The audience knows more than the characters in the

play, so that words and action have additional meaning for the audience; Socratic

irony is named after Socrates' teaching method, whereby he assumes

ignorance and openness to opposing points of view which turn out to be (he shows

them to be) foolish. Irony is often confused with sarcasm, but sarcasm is merely

one kind of irony; it is praise which is really an insult; sarcasm generally

involves malice, the desire to put someone down, e.g., "This is my

brilliant son, who failed out of college."

Jesuits:

The label Jesuit

is a common one applied to the Society of Jesus, a Roman Catholic order founded

by Ignatius of Loyola in the 16th century as part of the wider Catholic

Counter-Reformation. The motto of the Jesuits is Ad

majorem Dei gloriam ("to the greater glory of God"), and their

primary goal is to expand the Roman Catholic Church through preaching and

teaching. As a result, education has always been its primary activity. Jesuit schools spread across Europe and were instrumental in

preventing a number of regions from becoming Protestant. By 1640 they had more

than 500 colleges throughout Europe - after another century, the number reached

650 in addition to partial or total control of around two dozen different

universities.

Gottfried

Wilhelm Leibniz: In 1710 Leibniz published Théodicée a philosophical work intended to tackle the problem of evil in a

world created by a good God. He argued that the world was organized by a system

of “monads” or indivisible unities, of which the highest was God.

Since the system was created by an all-good, totally harmonious God, of

necessity the system itself was the best of all possible systems; within it all

events are linked by a chain of cause and effect.

Events that look evil or unjust to our limited view will ultimately be

found to cause greater compensating good. Leibniz’s

optimism is a prime target for Voltaire

in Candide.

Lisbon

Earthquake of 1755: This

earthquake was one of the greatest natural catastrophes of the 18th

century. Lisbon

was the fourth largest city in Europe and famous for its. Being a port city, seismic waves from the earthquake

inundated low-lying areas and a major fire destroyed many of the building which

had not been damaged by the quake. Estimates

of lives lost reached as high as 70,000 and estimates of housing damaged

suggested that only 3,000 of 20,000 dwellings had not been damaged.

Manichees:

A heretical

Christian sect with pre-Christian roots, the Manichees were troubled by an

apparent inconsistency in orthodox Christian belief. How, the Manichees asked,

could evil, from which we need to be saved, exist in the world at all, if God is

both good and omnipotent? The Manichean answer was that God was not omnipotent;

evil was an equally powerful force which God resisted, but could not eradicate.

The sect flourished from the third to fifth centuries, but an interest in

Manichean ideas was revived by Bayle.

Philosophes:

A French word, philosophes

eventually came to refer to a group of European Enlightenment thinkers who were

committed to the ideas of Deism and to social reform.

According to Richard Hooker, “The rallying cry for the

philosophes was the concept of progress.

By mastering both natural sciences and human sciences, humanity could harness

the natural world for its own benefit and learn to live peacefully with one

another

Alexander

Pope (1688-1744): An English poet best known for his mastery of the heroic

couplet, Pope also helped to popularize Optimism.

His Essay

on Man presents the idea of an infinite God who created the best of all

possible worlds and limited humans who should accept “'T is but a part we see,

and not a whole (i. 60).

The same epistle continues:

All

nature is but art, unknown to thee;

All chance, direction, which thou canst not see;

All discord, harmony not understood;

All partial evil, universal good;

And spite of pride, in erring reason's spite,

One truth is clear, Whatever is, is right.

( i.289-94).

Jean-Jacques

Rousseau (1712-1178): While Rousseau is a major figure of the Enlightenment, he is

in many ways the polar opposite of Voltaire.

Rousseau with his emphasis on emotions, his opposition to technology and

urbanization, and his contribution to the myth of the noble savage stands as a

forerunner of Romanticism.

Satire:

The word satire derives from the Latin satira, meaning

"medley." A satire, either in prose or in poetic form, holds

prevailing vices or follies up to ridicule: it employs humor and wit to

criticize human institutions or humanity itself, in order that they might be

remodeled or improved.

Theodicy:

Leibniz introduced the term “theodicy,” a combination of the Greek

words theos (god) and dike (order, right).

The term has since come to mean “a vindication of God's goodness and

justice in the face of the existence of evil.”

Understatement:

The opposite of hyperbole, “understatement” is “a statement

that is restrained in ironic contrast to what might have been said.” It too is

a weapon in the satirist’s arsenal.

Study Questions:

1.

How does Voltaire design the opening chapter to be recognized as a parody

of the Biblical story of the Fall? (Why would Voltaire be doing this?)

2.

What view of heroes and war are we given in the Bulgarian episode?

3.

How does James the Anabaptist differ from other religious figures that

Candide encounters? What do you think is Voltaire's point in the ending of

this episode?

4.

When Candide meets up with his old tutor Pangloss, the latter is in a

pitiable condition. How does he explain the cause of his woes in the light

of his principles of philosophical optimism? What are we to think of this?

5.

What were the circumstances of the Lisbon earthquake, and what trauma did

it pose for both orthodox Christian theology and philosophical optimism?

6.

The term auto-da-fé

means "act of faith." How does Voltaire use the term as irony?

7.

How does Candide come to be reunited with Cunegonde? What are the chief

episodes in her story of her experiences since the "Fall"? What

s her response to what has happened to her?

8.

Why does Candide have to flee Lisbon? What kind of advice does he

get from the Old Woman? (How does her use of Reason differ from that of

Pangloss, who is absent?)

9.

What kind of reasoning do the travelers engage in during the voyage from

Cadiz to Argentina and Paraguay ?

10.

What are the main themes of the history of the Old Woman? What does

this catalogue of disasters have to do with the overall theme of Candide?

What attitude does the Old Woman adopt towards what has happened to her?

What counsel does she give her companions on the basis of her experience?

What does Candide think the old woman's history means for the theories of

Pangloss?

11.

Who is Cacambo? How is he similar to the Old Woman? How is he

different? What advice does he give his master Candide?

12.

What are the outstanding features of the "Jesuit kingdom"

Candide and Cacambo visit in Paraguay? Why is Voltaire so hostile to this

community?) Whom does Candide meet there, to his great surprise? Why does

the encounter end as it does? What advice does Cacambo give his master?

13.

What mistake does Candide make in rescuing the girls from the monkeys

that are chasing them? What is the point of this episode?

14.

How do Candide and Cacambo avoid being eaten by the Oreillons (the

"Big-Ears)?

15.

How do Candide and Cacambo get to El Dorado?

16.

What are the important points of the history of El Dorado that are

conveyed by the old sage?

17.

What is striking about the religion of El Dorado?

18.

What is striking about the reception Candide and Cacambo receive from the

King of El Dorado? (

19.

What is the focus of intellectual life in El Dorado?

20.

What essential features of European civilization are absent from El

Dorado?

21.

Why does Candide resolve to leave El Dorado?

22.

What point is Voltaire making in the encounter Cacambo and Candide have

with the Negro they find on the way in to Dutch Surinam? What theological issues

get raised in the course of this meeting? How does Candide respond to the

Negro's story?

23.

How does Martin become the companion of Candide?

24.

How does Martin define his own philosophical perspective? (What

does he mean by describing himself as a Manichean?) How do his views differ from

Candide's?

25.

In Chapter 22, Candide and Martin encounter a scholar at the dinner

hosted by the Marchioness of Parolignac. What is Voltaire up to in

designing this conversation?

26.

What is the hoax played by the Abbé? How does the pair escape?

27.

How does Martin's view of England compare to his view of France?

What is the point of the episode in which Candide and Martin witness the

execution of Admiral Byng?

28.

What do we learn from the stories of Paquette (on the life of a

prostitute) and Friar Giroflée (on religious faith)?

29.

Who

is Pococurante? Why is his name fitting?

30.

What do Candide and Martin learn at the dinner with the six strangers at

the public inn in Venice? Who turns

up, in what circumstances? What is familiar, in the tale we've become

acquainted with, about the kind of story behind this surprise reappearance? What

is Martin's view of the sufferings of the six? Who has the most convincing

case - Martin or Candide?

31.

How does everyone in the little society come to be all gathered together

at the end?

32.

What are the themes of Pangloss' story? What are we to think of the

explanation he gives of his refusal to recant?

33.

How does the story of Candide and Cunegonde satirize the conventions of

romance at this point?

34.

What is the Baron's response to Cunegonde's demand, and Candide's

response to the Baron?

35.

How does the Dervish's initial reply undercut the assumption of

Pangloss's opening question? How does the sequel explain the rationale of the

rejection of that apparently eminently sensible assumption?

36.

What is the significance of the Sultan's attitude towards the mice in the

hold of the ship? (What is the Sultan presumably

concerned about?) What is the implicit advice in this parable for mankind?

37.

How does Pangloss' reply indicate that he hasn't heard what the Dervish

has been saying?

38.

What is the Old Turk's advice? What does it mean?

39. What do you make of the closing sentence of the conte? Has Candide changed? How?

40. Why is the particular setting significant?