MARKETING WISDOM OF

DAGWOOD, HAGAR OR CHARLIE BROWN

by

Herbert Jack Rotfeld

Professor of Marketing

Auburn University, Alabama

An historical review of introductory marketing textbooks presented at a conference Spring 1998 highlighted supposed milestones in this area of publishing. Obviously, any study of more than seven decades of textbook content and changes does provide some insight into an academic field and indicates what faculty of a period considered important. Yet, as with much of historical analysis, the selection of items highlighted and general assertions also indicate the academic philosophy and views of the reviewer. In this presentation, lengthy and repeated mention was made of the three innovations as important "milestones" in the textbooks: use of cartoons to present the material, color pictures, and computerized test banks with instructor packages.

"Millstones" might be a more apt term.

The presenter asserted that "Marketing is [increasingly] respected in the academic environment," but these innovations, or maybe the fact that they might be considered positive contributions, are reasons why many other departments consider business programs a drain on the intellectual abilities of a university, with some business teachers holding doctorates yet almost acting anti-intellectual.

History or English classes have students read books, which are then analyzed and discussed, while marketing's focus is on students remembering textbook "facts." A University should focus on thinking, but our textbooks are filled with lists for students to memorize. They have students read; our books have cartoons and color pictures. Their students write essays; our students answer multiple-choice exams or socially loaf through group projects.

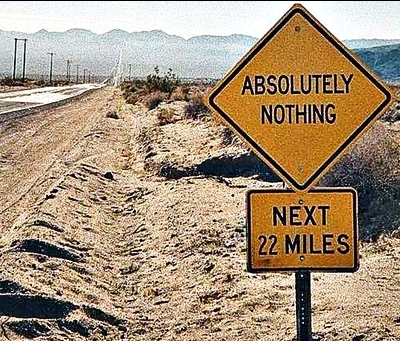

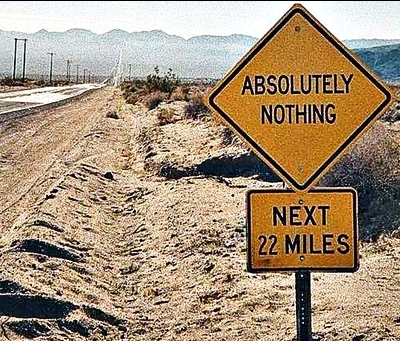

Cartoons are read, sometimes more readily than the text. Noted creative genius and leader of the advertising business, David Ogilvy, insisted for many years that humor harms advertising effectiveness in that people remember the joke but not the more important brand or message. A decade ago, with a front page headlines in Advertising Age, he said humor could be used, but with extreme care. In a comparable vein, textbook cartoons can help illustrate a point, but students might ignore the point and remember the cartoon. Students top-of-mind recall of the most recently read chapter could now often be a joke or picture instead of the point they were trying to highlight.

Similarly, color gets attention and can make reading more

interesting.

Even the New York Times now has color pictures. But the use of

color

has a danger as the style can take precedence over the substance of

what

the color was intended to enhance. And therein lies a problem.

Sometimes

marketing classes get more concerned with style than substance.

I will admit to having a love-hate relationship with the now-ubiquitous computerized text banks. As classes get larger, I use them more and more, yet I see the dangers: many of the questions are drawn from sometimes-trivial details of checklists, and the more they are used they encourage the students to consider lectures irrelevant. They encourage faculty to lecture without much mental involvement in either the material or the students. After years of classes that used this "innovation," students are likely to sit with textbooks open and markers in hand, coloring sentences bright colors where the instructor mentions it as important.

At a more basic level, since students are seldom told why they should learn, they often misunderstand the importance of education or what they might take away from the course.

A student frustrated me greatly last year. Always prepared for class, she had top grades on pop quizzes and knew the answer when called upon. But no matter how much I begged or cajoled, I could not get her to participate in class discussions. She would answer my direct questions and no more. When asked before class one day, she simply said that rarely are student comments part of exams, so she only wanted to concentrate on what I had to say. Based on her learning skills from other courses, class time was when she would try and discern what she needed to know for exams. In the end, all she wanted was credit from the class for her certification of a marketing degree.

In reality, a successful career requires a facile and educated mind, not specific information that any book might contain. The classroom experience should have more value than just the credit and grades from exams. Faculty fail to strongly and repeatedly tell students that the abilities to think and write clearly are more important than the textbook's checklists. As noted by Ed Golden of Central Washington University, "We have to be an English teacher, we must be a speech teacher [so students learn] important skills."

With a primary focus on general content, style or form, the textbook review was missing a statement of what those books mean for education. Listing topics and their proliferation could (but did not try to) explain why, as Gary Mankelow and Michael Jay Polonsky's survey found, so many marketing faculty doubt whether our discipline has a central or common theory.

Instead, the history revealed the evolution of textbooks as a method of increasing the fun for students and making teaching an easier activity. That is the concern of many faculty who see students as customer who "buy" our courses and degrees. And somehow, the end loser could be students in our classes.